Endnotes

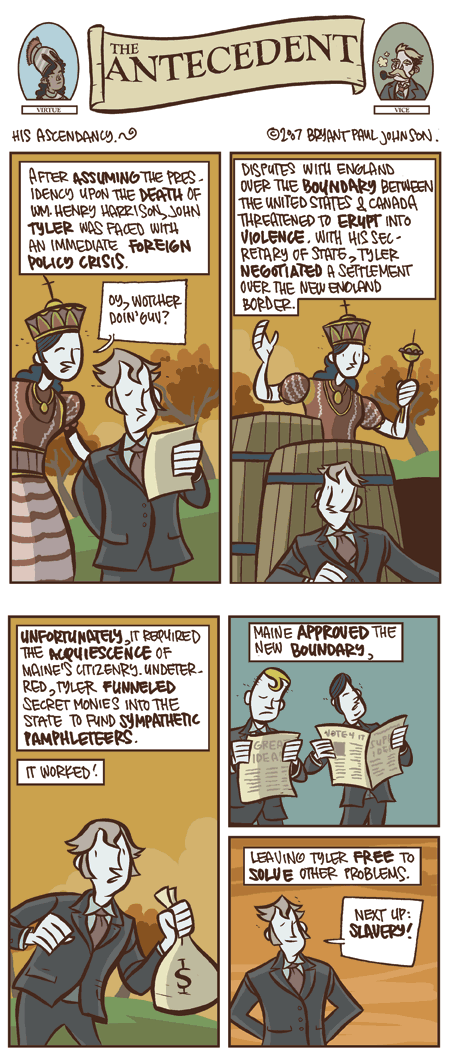

John Tyler inherited the Presidency following the death of William Henry Harrison in 1841, just a month after Harrison’s inauguration (Harrison -at that point the oldest man to take the office of the Presidency- caught a fatal cold giving his inaugural speech). Though there were contingencies in the Constitution of the United States for such an emergency, this was the first instance. He was pejoratively called “His Ascendancy” by those who believed that there should either be a new election or a vote by the House of Representatives. The only other Whig elected president -Zachary Taylor- would also die in office less than a decade later.

William Henry Harrison (“hero” of the War of 1812) and John Tyler ran for election in 1840 for the nascent Whig Party on a platform of “we’re not Martin Van Buren” (see The Antecedent #9). Tyler, a lifelong “Jeffersonian Democrat” split from the Democrats over ethical conflicts with Andrew Jackson. When he assumed the presidency, he veered sharply from the Whig platform leaving him without a party shortly into his one term.

I’m pretty sure that Queen Victoria didn’t speak with a mock-cockney accent.

Even after two wars with the British, the border between the United States and British Canada was still nebulous. Those members of the United States government given towards histrionics believed that the British were intentionally baiting the United States into open conflict. Sadly, the President was one of those members.

The negotiation over the border between New Brunswick and Maine was conducted by Tyler’s Secretary of State Daniel Webster and Webster’s friend Lord Ashburton; it required approval from the voters of Maine as it involved the transfer of property. Tyler used secret discretionary funds to pay sympathetic newspapermen in Maine to tout the treaty’s benefits. Tyler considered himself an ardent states’ rights advocate as well as a strict Constitutional Constructionist; to subvert the state politics of Maine with federal funds was an act of ethical gymnastics; thankfully this type of soft-news chicanery is no longer typical of politics.

Incidentally, Tyler also secretly funded a so-called “ambassador of slavery,” who travelled foreign courts seeking to minimize foreign meddling in the practice of slavery. Tyler suspected that the abolitionist movement in the United States was a ploy by the British to weaken the economy of the United States and pave the way for re-annexation of their former colonies.

He was big into secret funding.

He didn’t “solve” slavery though (you know, since he was elected a member of the Confederate Congress).

Bibliography:

The Age of Jackson, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Back Bay Books, 1945

James K. Polk, John Seigenthaler, ed. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Times Books, 2004

John Tyler, The Accidental President, Edward P. Crapol, UNC Press, 2006

Martin Van Buren, Ted Widmer, ed. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Times Books, 2005

Comments are closed.