Endnotes

Prior to his presidency, Martin Van Buren earned the nickname “The Little Wizard” for his political maneuverings behind the scenes. In the election of 1824 in which John Quincy Adams was elected president when the final decision went to the House of Representatives (see The Antecedent #7), Van Buren campaigned on behalf of William H. Crawford, who despite having suffered a stroke just prior to the election still earned enough electoral votes to finish in the top three (behind Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams).

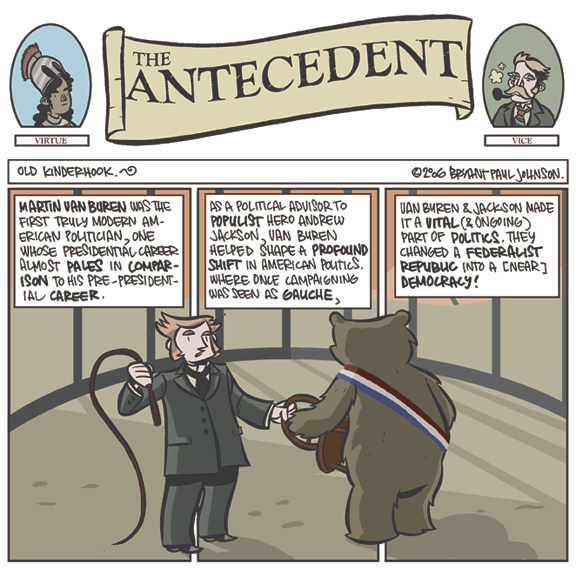

For the 1828 election, Martin Van Buren campaigned with General Andrew Jackson, hero of the War of 1812. Though geographically divided (Van Buren was a New Yorker while Jackson gained fame and fortune as a Westerner [which in 1828 meant someone from Tennessee]) they found common ground in Jackson’s charismatic populism. Both Jackson and Van Buren believed that the United States shouldn’t be controlled by the political and economic elite, but by the very people whose labor propelled it (minus of course, women, blacks and Indians).

Jackson and Van Buren campaigned tirelessly, traveling the country to build grass-root support. In doing so, they inadvertently transformed the path to the presidency: prior to Andrew Jackson, the path to the presidency required the blessing of the political leadership; the will of the people was second to approval from the will of the old Jeffersonians. Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren changed all that, making the presidency a popularity contest (which is pretty much where it stands today; well, popularity contest coupled with a fundraising contest). Of course, in a true democracy, office is a popularity contest; one in which you hope that the best qualified candidate happens to be the most popular.

Van Buren was the ultimate political chameleon. As a rising star in New York politics, he cultured relationships with powerful politicians for personal gain. Once in Washington, he did likewise. Though a Northerner (and perhaps a cryto-abolitionist to boot!) he went out of his way to tour the South and make powerful friends with the entrenched slave powers. Like the best of modern politicians, he could talk for hours without ever seeming to say anything; or more importantly, without offending potential voters. He skirted the slavery issue (a political necessity if one hoped to build popular support nationwide) building Andrew Jackson’s appeal North and South of the Mason-Dixon line (political candidates were still largely regional in appeal; what Van Buren and Jackson succeeded in doing was creating a nationwide base despite the slavery issue).

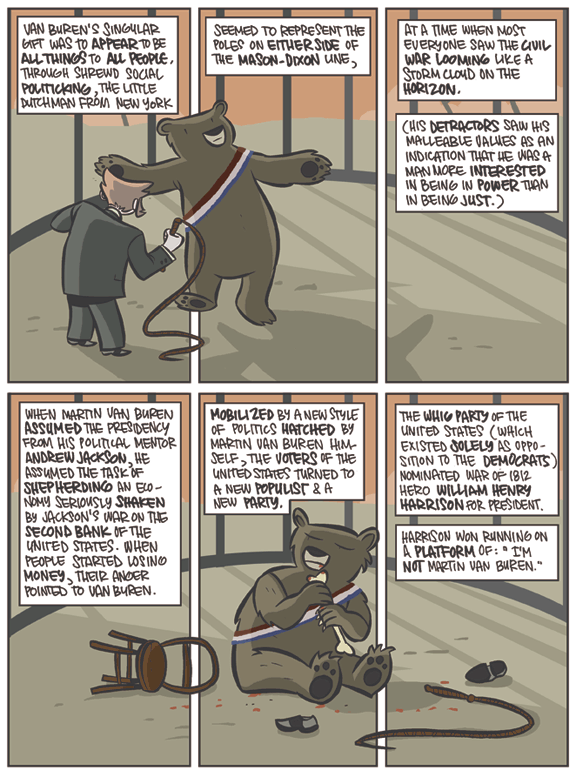

After Andrew Jackson’s war on the Second Bank of the United States (the details of which were discussed in the The Antecedent #8), the economy of the United States took a turn for the worse. Martin Van Buren the newly elected President of the United States was unfortunate enough to come to office in a time of economic recession. And since he was an integral part of the war on the Second Bank (as Jackson’s Vice-President and protege) he was saddled with the blame.

Martin Van Buren was an easy man to spot. He was short, stout and topped with an elaborate head of hair. To many people who voted for Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren was too aristocratic: he was cartoonishly foppish at a time when people losing great sums of money. In an era of increasing political scrutiny (and the dawn of a glorious age of political cartooning), Van Buren’s public persona was a liability. One seized upon in the 1840 election.

William Henry Harrison was a politician with little substance beyond his status as a successful military leader during the War of 1812. The Whig Party (the name was borrowed from the Whig Party of Great Britain, the opposition part in Parliament at the time) nominated him hoping that Andrew Jackson’s populist archetype would again resonate with voters (though Harrison was hardly cut from the same cloth; his military heroics were modest in comparison; mostly involving slaughtering Native Americans). The Whigs painted Martin Van Buren as an aristocrat out of touch with the common man (though Van Buren was entirely self-made, born from very humble beginnings). When someone from Van Buren’s campaign mocked Harrison for his rough character (the famous “log-cabin and hard cider” epithet) the Whigs used it as a rallying point. Borrowing the best techniques from the Van Buren/Jackson strategy handbook, the Whig mobilized the electorate and won the election.

Recent Comments