In celebration of Steampunk Month here at ComixTalk, I’ve decided to take on the task of reviewing Warren Ellis’ FreakAngels. Be warned, though: if "steampunk" to you means stovepipe hats, pocket watches, and parasols, then you may be a little disoriented by the direction Mr. Ellis takes his comic.

But then again, beyond the cutesy wordplay on "cyberpunk," what’s steampunk, anyway?

To me, steampunk represents the genre that I desperately wanted to love. When I was a tot, other kids would build models of Ford Mustangs or F-14 Tomcats. Not me. On my bookshelf, I proudly displayed models of the Monitor and the Merrimack, two metal-clad warships that engaged in battle during the American Civil War. A major part of my obsession with the ironclads was because they looked like something Jules Verne would have built — the Monitor, especially, looked like a smoke-spewing waterborne tank. The age of wooden vessels with billowing sails and woodcarvings of beautiful women at the bow was violently thrust into the gritty world of coal, iron, and propellers.

Thus, when I finally became aware of the steampunk genre, I determined that this — THIS — was the sci-fi subgenre for me. Overly ornate Jules Verne-inspired flying machines? Dapper gents and ladies in fancy hats palling around with clockwork robots? I’m totally there! Every piece of steampunk media I tried, though — which included Paul Di Filippo’s The Steampunk Trilogy novel, the Aracanum video game, Kia Asamiya’s Steam Detectives manga, Neil Gaiman’s Mr. Hero the Newmatic Man comic book, and the Legend TV show — all seemed to fall short of my expectations. It was frustrating to get rebuffed like this, as if a girl you knew you were perfect for kept sneering at you icily.

Why won’t you love me back?

As you can infer from the cover of this month’s ComixTalk (what with its saucy automaton laboring on public works in Ancient Rome), everybody has their own unique version of what steampunk should be. There is no common ground, really. My own version of steampunk is rooted in the science fiction stories developed at the turn of the 20th Century — a world where H. G. Wells’ tripods run amok in London and where Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s android Hadaly (invented by a mad scientist named Thomas Edison, of all people) seduces lovesick men. For some, the ideal vision of steampunk may incorporate elements of the American Wild West. Others, inspired by the fairy tales of the Victorian Era (Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan), like their steam punk with magic. Yet another set of fans want to see their steampunk populated by giant monsters, an homage to speculation that arose from the discovery of dinosaur skeletons and fueled by Arthur Conan Doyle’s Lost World.

And then there’s comic book author Warren Ellis, who no doubt would think my ideal, romanticized view of steampunk to be fooking preposterous. "Are you daft, man? That material is much too sentimental," he’d no doubt scoff between manly swigs of bourbon. You see? That’s why he has that rugged beard and I have this prickly growth on my chin. When Warren Ellis writes steampunk, he deemphasizes the "steam" and goes straight for the "punk."

I’m ashamed to admit this, but — despite Ellis’s undeniable prominence in the modern day comic book industry with legendary runs on The Authority, Planetary, Transmetropolitan, and Nextwave under his belt — I don’t have much first hand exposure to Warren Ellis beyond the small samples posted by Scans Daily folks. (And, boy, do those guys have a massive man crush for that Spider Jerusalem douchebag.) Yet there’s consistency in the tone of all his works, as if Ellis were a bitterly sarcastic college professor who, nevertheless, can’t hide his unbridled enthusiasm.

Consider this gem of a line, spoken by a FreakAngel named Luke: "What is the nature of time? Does time have a shape? Is it an arrow, or the rootball of a tree? Or perhaps some enormous floating bum, and us all swept up in the momentum of its colossal, unearthly farts." That sums up the Ellis experience: a queasy mix of intellectualism and shameless vulgarity and drenched in an overpowering British flavor with some dry humor on the side for good measure.

In a strong departure from the majority of steampunk stories, FreakAngels takes place in a post-apocalyptic future. During an interlude, Ellis muses that disaster fiction is a peculiarly British thing. (Tell that to the Japanese.) The Thames has flooded. The London Eye and the Millennium Dome are now partially submerged. Society has reverted to a state circa the Industrial Age, including the return of steam-powered vehicles. Anarchy seems to have been narrowly stemmed. The details of the catastrophe, which happened six years prior to the start of the story, are still unclear, although I’m willing to bet that the world didn’t suddenly get taken over by a bunch of steampunk cosplayers brassed that the Dome’s been officially renamed The O2.

The FreakAngels operate in the London city district of Whitechapel, a place that looks like it never left the 19th century in the first place. They are a gang of twelve who have known each other since childhood. But there’s more to the FreakAngels than just matching outerwear. They seem to possess dangerous psychic powers, ranging from mind reading to clairvoyance to all-out mind control. The condition does strange things to the body: FreakAngels have purple eyes and pasty white skin even if genetics says that their skin should be soaked in melanin. It’s implied that these powers are responsible for the world turning out the way it has, though the populace themselves are unaware of any involvement.

Each FreakAngel copes with this new society in a different way. Some use their powers to indulge their basest instincts. Sirkka, for example, is never seen outside the room where she is the conductor of a large orgy. Another FreakAngel, Arkady, seems to have lost her mind. Most of the FreakAngels, though, choose to use their powers to atone for what they did. Kirk maintains a look-out tower to watch for invaders, while Karl tends a garden to provide fresh food to the people of Whitechapel. Others deliver supplies and maintain much needed city services. Ellis described this series in shorthand as "Youth gone wild," but in reality it’s about youth taking responsibility for their sins.

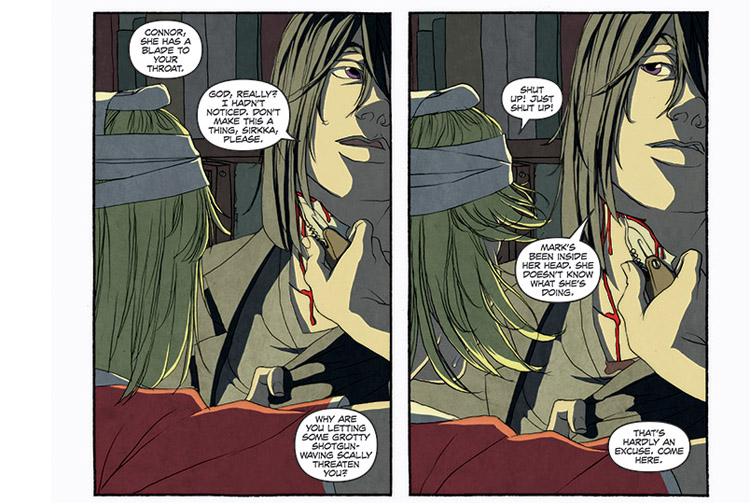

And then there’s Mark. He’s the thirteenth FreakAngel. Ominous. While he’s yet to make an appearance in the comic, his mere existence already has had a strong impact on the story. Expelled and presumably killled, Mark has surfaced outside the borders of Whitechapel. He murders two gunrunners after he’s discovered skimming the profits, and he mentally reprograms the brain of their sister, Alice, to kill the other FreakAngels. And this is where the story starts: Alice, who is both justifiably angry at her brothers’ deaths and under Mark’s control, confronting the FreakAngel Connor on the streets of Whitechapel.

Artist Paul Duffield brings a subversive style of grittiness and melancholy to all the characters. They’re all attractive people, mind you, even the one bald girl. There is, however, a sense that none of them are quite healthy. Their skin is pale, their posture a tad gaunt, as if they were either diseased or heavily medicated. Despite being young people in their 20s and 30s, their faces appear permanently sour and aged. It’s a perfect compliment to the writing. I don’t know how he does it, but Ellis manages to get paired up with superb artists, e.g., John Cassaday and Bryan Hitch, who have a knack drawing bleary-eyed, world-weary characters.

The story thus far moves along fairly well. It’s simply a string a character vignettes. We first follow KK, the poster girl for FreakAngels, as begins her day. Next we meet up with Connor and Alice, and then it’s off to meet the other characters. This does a great job developing the character traits and backgrounds of the story’s multiple protagonists. Ellis doesn’t set out to make the characters likable. Instead, he challenges the readers to see these characters as real people with real motivations, no matter how petty. Luke, for example, is only on good behavior because he’s afraid of the punishment. Yet, when no one’s look more than willing to use his power to bend the will of his ex just to get a nice place to sleep. Luke is despicable precisely because he’s the kind of creep someone might encounter in real life.

At the same time, we’re introduced to several mysteries. The large scale ones — Mark’s sudden reappearance, the devolution of the the world’s technology — take front and center, but like the Smoke Monster on Lost, we expect such mysteries to unravel gradually over the course of the comic. The smaller, character specific mysteries are just as intriguing. What was the romantic liaison between Sirrka and the steamboat captain like? What happens if Arkady loses control of her powers? When the characters are as eccentric as the ones in FreakAngels, you can be sure there’s plenty of stories to be mined.

The dialogue in FreakAngels is an absolute treasure, a cut above prose you’d find in most novels. When we first hear Alice talk, she rattles off a litany of British vulgarities: "I bet, you wanker! He killed my family and I’ve walked all the fooking way down here to hill his! You just stand there! You just stand there and let me kill you!" If I hadn’t known Ellis was himself from England, I — in my typical American state of ignorance about international vagaries — would have concluded that she were acting like a stereotypical Brit. Beyond that, each character has their own individual way of saying things. KK speaks with an air of snark and bemusement, while Sirkka can seem downright aristocratic. If FreakAngels were reduced to only the text with nothing identifying the speaker, it wouldn’t be a synch to tell which character was doing the talking.

Ellis’ reputation as sociocultural writer is well deserved, and he pours his heart and soul into FreakAngels. In a way, the story is anti-steampunk. Most steampunk works are set in an age of science while FreakAngels takes place in a world plunged back into ignorance. If you step back, though, a lot of the core themes emerge: the elbow grease inventiveness, the world that needs discovery, and, of course, those damn sexy corsets.

Comments are closed.