I would guess that most comics readers in the US don't read works published outside the English speaking world (US, Canada, UK) or Japan. A trickle of European works make it to print in translation every year, but it is not even a small percentage of the work published. I've explored French language comics (bande dessinee) a bit in print but not online. What is out there in webcomics (webbandedessinee?) from Europe?

One great site to explore is Electrocomics, which hails out of Germany, founded by comic artist Ulli Lust in 2005. Electrocomics touts itself as a "screen comic publisher" offering a large selection of comics as pdf downloads, many in English translation. I'll just take a look at two of their more recent offerings.

Rubiah from the Swiss-born Belgian Sacha Goerg is an autobiographical account of the author's holiday in Indonesia drawn in a loose and sparse black line. The narrative covers an indeterminate amount of time divided up into 6 sections. The first section shows the protagonist and his friend on a bus, probably crossing the border. The protagonist is cleanly shaved, head and face. The second section finds him at a beach side dwelling, with hair grown out and a scruffy beard. We are simply and directly shown the passage of time.

A sense of anonymity pervades the work. Characters are named but we learn nothing about them (not even the protagonist/author). The whole story is shown without any narrative captions or interior monologue. What comes through during the slow course of the story is a sense of atmosphere: the lazy, beach-side paradise where a number of visitors live out idle days and nights. No great dramatic moments are to be found, yet the work as a whole is so lovely and almost wistful, as if you were looking back at your own vacation, that the reader is entranced.

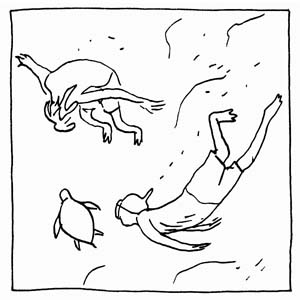

Goerg's artwork is amazing in its simplicity, using minimalist representation to great expressive effect. Everything is drawn with a thin pen in black ink: no filled in black areas, just loose hatching and scribbles. He employs the most abstracted representations to build the sense of place through the natural surroundings and create an emotional atmosphere. Let me point out a few particularly effective or attractive examples. A swimming panel, very sparse, but filled with movement:

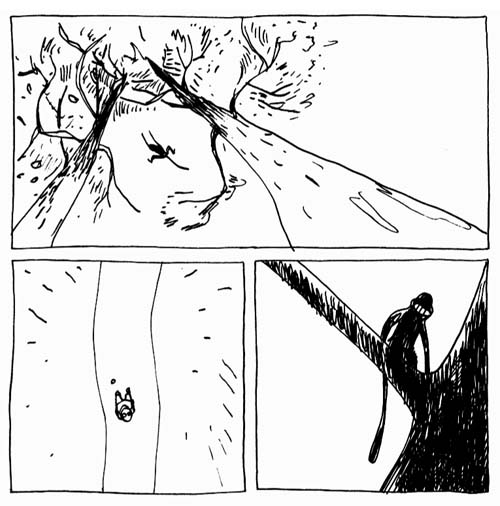

I love the powerful geometry of the lines in this page, the sense of space, and that kind of spooky monkey shadowed against the sun (the monkeys are recurring characters throughout the story):

In a nighttime scene, George adds a scribble line over faces and bodies (and occasionally backgrounds), blurring out the contents of the panels, recreating the sense of low light:

Rubiah is worth spending some time reading, and in one convenient download you don't have to wait for page loads.

Almost diametrically opposite from Rubiah is Kai Pfeiffer's Radioactive Forever: A Comic Strip Essay. While Goerg's comic is minimal and peaceful, an autobiographical story of quiet paradise, Pfeiffer's comic is a non-fictional essay, didactic and garish, a hellish narrative.

Radioactive Forever tells the story of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor accident in 1986. Pfeiffer starts with the event and then moves forward to address the ongoing conditions in the area as well as the resurgence of nuclear power as answer for the emerging energy crisis. He addresses the way the fear of nuclear power has decreased over the years through the passage of time and a sense of familiarity. After worrying for so long the fear lessens and now we see calls for more nuclear power (talk of it on NPR this week, even, in regards to the Presidential candidates). In this way the comic is a propagandistic work, meant to inform and influence readers. I've never known many details on the Chernobyl incident, so I learned the historical background. How effectively the work would be in swaying a reader's views is hard to gauge, as I am already on the "no nuclear" side.

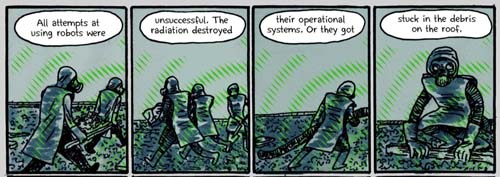

The comic itself is a bit of a hodgepodge, using both traditional and computer techniques, in an art style that is reminiscent of work by some of the Fort Thunder artists, occasionally appearing to veer from purposeful (skilled) crude art to slightly unskilled crude art. It is an almost uncomfortable mix that is appropriate for the subject. Pfeiffer uses a lot of color in an often murky kind of way. A great example of this is a scene where soldiers are trying to contain the reactor:

The colors smudge together creating a dark and foreboding atmosphere. The green pulsating lines offer a classic representation of invisible energies. There is a superhero-esque appearance to this scene with the men in masked costumes and the bright energy, yet the actualities of the scene are a horrifying about face from any generic superheroics. These men were called "human robots" allowed to stay on the roof of the reactor only two minutes after which their protective gear was useless. The superhero trope is also used throughout in the form of "Nuclear Boy" who begins life as a young advocate for atomic power in the 50s and becomes an old man in the 80s, traveling through the "Forbidden Zone" around Chernobyl and seeing what has been wrought by the disaster.

Some of the computer effects are poorly used, too many glowing gradations, but in showing the reactor's explosion a black page is pierced by a glaring white point of light at the center of some pink and yellow explosion lines. The white of that explosive center on a field of black is almost like a light shining out from behind the page. The effect is powerful.

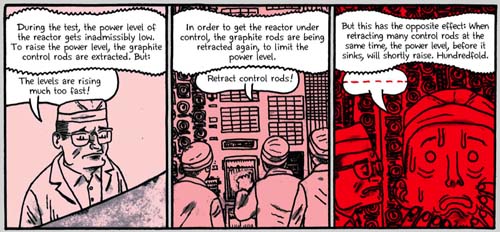

In the lead-up to the explosion, the previous page has three monochromatic panels that shift from light pink to pink to bright red. Pfeiffer uses a few of these series of monochromatic panels, though the one below is the most visually relevant sequence.

There is a certain disjointed aspect to the whole work. Sometimes narration appears handwritten in the panels, while at other times it is typeset above or below the panels. Sometimes there is a single image per page. Other times there is one row of two or three panels in the center of the page, and rarely there are multiple rows of panels that fill the page. In a similar way the narrative jumps around from telling the story of the Chernobyl incident to discussing the fall-out year later, to discussing the resurgence of nuclear power and propaganda around it, to a self-critique of electrical over-consumption.

The image above (one of the least discordant images in the comic) starts a sequence of the author using all kinds of electrical devices (stereo, videogame, computer, electric shaver, electric toothbrush). This sequence nicely brings the "over there" distant concept of Chernobyl into a more personal context (vital for making any kind of didactic point).

Radioactive Forever is a strange and powerful work, though I'm not sure in the end how successful it can be in its mission. The crudity of the art, despite its charms, would turn off a lot of comics reader, let alone non-comics readers.

These two works are only a small sampling of the work to be found at Electrocomics (in English). I'd also highly recommend works by Ulli Lust, Frederic Coché, and Oliver Grajewski.

Recent Comments