Endnotes

James Monroe’s election to office in 1816 ushered in a period of American history commonly known as “The Era of Good Feelings.” With the political dissolution of the Federalist Party (see The Antecedent…well, basically all of them up to this point) the Republicans (or theDemocratic-Republicans as they had come to be known) ran virtuallyunchallenged in the federal election, receiving all but one electoralvote. (“This Era of Good Feelings” wouldn’t last, though this is a tale for Antecedents yet to come.)

After the brouhaha of the War of 1812, relations with Great Britain had more or less normalized (trade continued, even if British foreignministers still didn’t recognize the United States as a country of equal footing). The issues that had nearly torn the United States apart (or rather, torn New England from the rest of the country) had become moot. Except for slavery. That issue was still a few decades from resolution (President Monroe’s Missouri Compromise of 1820 put off the issue for a few years more).

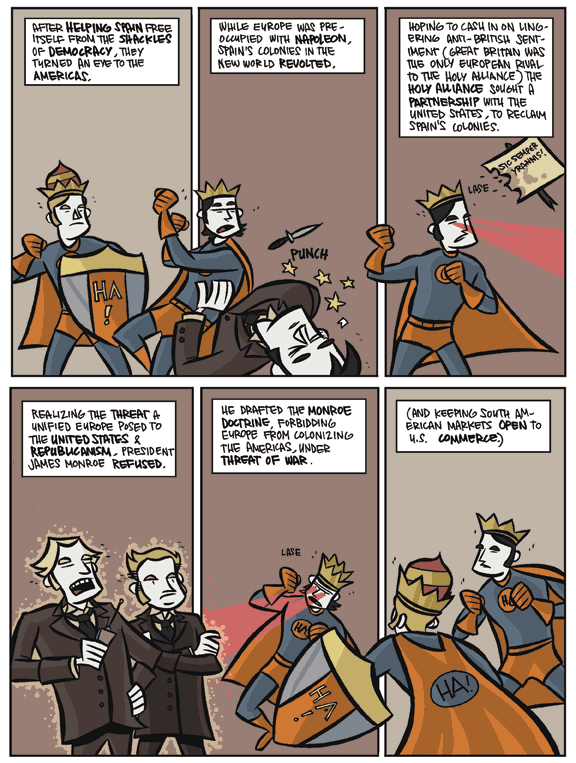

During the Napoleonic Wars, a number of Spain’s colonies in SouthAmerica had cast aside their ties to Spain’s monarchy and began forming republican (as in “without a king”) governments. The United States was eager to sow republicanism in the world, yet was still partially bound to the needs of Europe’s monarchs. The United States needed to walk a tightrope: encouragement if not outright recognition of new republics to the south while trying to maintain favorable relationships with France and Spain to facilitate purchase of their territories in North America (Spain/France/Spain again owned the Florida Territories; France/Mexico owned lands west of the Mississippi river). With the purchase of Florida in 1821, the United States was free to exercise its foreign policy muscles.

South America represented a huge source of raw material for the international marketplace. Apart from produce and way points for sailing vessels, it was a major sources of the precious metals that kept the worlds economies flowing. A direct link to a European power meant that all commerce in a particular South American country flowed through the monarch. Anyone wishing to trade with said South American country funneled money through the king. To Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, this represented an anathema to his New England mercantile instincts: a direct tie to a foreign power was in essence a monopoly partnership. Eager to increase the United States’ power in the world’s marketplace, Adams sought an end to Spain’s dominance of the New World.

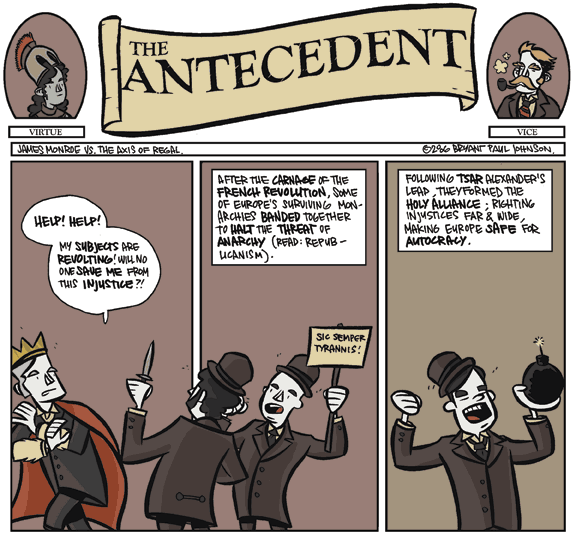

In 1815, to combat Napoleon’s army in Europe, an alliance was created between Great Britain, Russia, Austria and Prussia. When Napoleon was defeated, Tsar Alexander created the Holy Alliance out of the alliance (excluding Great Britain, who represented the only European super-power left standing and the encroaching influence of popular government). Tsar Alexander’s Holy Alliance was devoted to the proliferation of peace through the teachings of Christ (though presumably not the heretical Christianity of Anglicanism). Before long, their umbrella covered all the monarchies in Europe save Great Britain.

Though couched in the rhetoric of “peace,” the Holy Alliance served primarily to maintain the powers of monarchies. To the Holy Alliance, popular government meant anarchy and bloodshed. And probably also the head of a monarch decorating a pike. With their combined power, the Holy Alliance helped quash republican movements in Piedmont and Napoli and helped Spanish King/Napoleon’s Poppet Ferdinand VII regain political power after the constitutional movement of 1812 had pushed the kingdom towards representational government.

The Holy Alliance sought the United State’s help in subduing the South American “Juntas” in 1819. Like the United States, Great Britain wanted a better economic deal with South America. The Holy Alliance hoped to use fear of British encroachment to create an alliance with the United States. Fortunately, President James Monroe had as his secretary a very capable foreign diplomat in John Quincy Adams. Adams recognized the political and economic threats that the Holy Alliance represented, and urged President Monroe to refuse. Monroe and Adams felt it was better to side with Great Britain against the Holy Alliance (and help draft the economic terms in a new South America) than to pick another fight with the British.

In early 1823 Tsar Alexander made a proclamation asserting Russian rights of trade on the Pacific coast of North America (where Russian settlements had existed for years). According to Russia’s proclamation, all trade above the 51st parallel on the Pacific coast of North America required the Tsar’s approval, under penalty of confiscation. Still smarting from years of abuse at the hands of the British Royal Navy, this proved the last straw. In December of 1823, before Congress, President James Monroe (aided by John Quincy Adams in the drafting) outlined his Monroe Doctrine. It put forth the notion that any attempts at colonization in the Americas by any foreign power represented a direct threat the the well-being of the United States and would be viewed as an attack.

It was a bold and potentially risky move: the United States, though militarily superior than it had been during the War of 1812, wasn’t prepared for a war against the combined monarchies of Europe. It did, however, have the tacit support of the Holy Alliance’s European rival Great Britain (presumably, Great Britain’s naval support for the measure [as well as its long entrenched pseudo-republican constitution] excluded Canada from this declaration). I’m pretty certain that the Monroe Doctrine did not give American presidents (and their secretaries of state) super-powers.

Recent Comments