Endnotes

Andrew Jackson’s split with the establishment of the Democratic-Republican Party (formerly the Republican Party) created the modern Democratic Party. The rest of the party continued on, but mostly as an opposition party (first as the National Republicans, later as the Whigs).

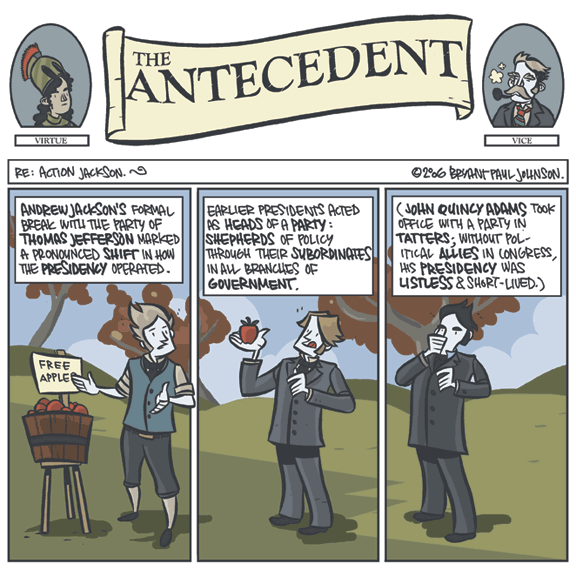

Looking at the first six presidents, those who proved successful (basically all but John Adams and John Quincy Adams) served as the heads of their respective parties (though George Washington was technically without a party, he was the de facto head of the Federalists), marshaling support for their legislation through the House and Senate (John Adams and John Quincy Adams, both iconoclasts, clashed with the opposition and their own parties, making their jobs infinitely more difficult). Jackson was the first successful president to overcome strong opposition in congress.

Jackson’s prime legacy was the notion of a government open to all citizens (which, of course, was a pretty closed group to begin with). Jackson dismissed the idea that government needed to be peopled with the so-called elite members of society (contrary to what we may have learned in your middle school history classes, the government of the United States was never intended to be a democracy in the literal sense; it was intended to be a republic that reflected the needs of the people, but without the butterfly whims of an uninformed citizenry; government “by the people” was a pejorative along the lines of “mob rule;” looking carefully at the Constitution as it was drafted, we see many instances of structure intended to keep government and “the people” at arm’s length, the best example being the electoral college). In Andrew Jackson’s view restricting the government to the social, political and economical elite created a disparity between the wealthy and the poor. Those in power used their power to keep the status quo; government itself became an engine of exploitation (this notion needs to be tempered with the idea that Jackson was a slave-owner; his idea of exploitation covered only those deemed actual citizens; he wasn’t afraid of muscling non-citizens out of the way for the advantage of the poorer, but whiter inhabitants, even if they had the law on their sides, as the Native Americans did).

From his first speech to congress, Andrew Jackson made it clear that he wouldn’t stand for the abuse of working class by the economically advantaged. Restructuring the Second Bank of the United States became the cornerstone of his time in office; pitting his popularity as a war hero and populist against the entrenched powers in government, many of whom had financial and political interest in the well-being of the Second Bank. Jackson wouldn’t be enjoying the relationship with congress that made George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe’s presidencies so successful.

Andrew Jackson also made it clear that he’d be rewarding loyalty. While other presidents made a show of conciliation to the defeated parties, by keeping able, if not politically similar, people in government position when they took over office, Jackson stacked his cabinet and offices with loyal Democrats. When people in his own cabinet no longer supported his policies (or were undermining them in their own quests for future political power as was the case with Vice-President John C. Calhoun) he kicked them out.

The defining event of Andrew Jackson’s political career was the battle with the Second Bank of the United States. It would transform the economic future of the country, and the means in which the president could shape domestic policy. The Second Bank of the United States had a twenty year charter set to expire in 1836. Though much of the country didn’t benefit from the Bank directly (agricultural and rural interests were usually met by local banking institutions), most people deemed the Second Bank a necessity to facilitate economic expansion. Jackson saw it as a villain: by seemingly capricious whim (and with minimal government oversight), it could ruin men, all for the gain of its shareholders (many of whom were foreign), and with funds provided by the federal government.

The Second Bank had tremendous influence in government (and if allegations were to be believed, powers beyond just indirect influence); when Jackson made remodeling the Second Bank a priority, the Bank’s loyal politicians pulled out all stops in their attempt to renew the charter, turning it into an election issue. A vote for Jackson’s re-election in 1832 meant a vote for economic anarchy (in the words of Bank President Nicholas Biddle). Jackson, ever popular with the average (and perhaps less affluent) citizen won the election. Congress passed a bill to re-charter the bank sending it to the president for approval. Jackson vetoed the bill.

Previous presidents had used the veto as a constitutional safeguard (perhaps encroaching upon the purview of the Supreme Court): early presidents vetoed bills they thought contradicted the laws (and spirit) of the constitution. The Second Bank of the United States’ charter had been upheld by the Supreme Court in 1819; it was constitutional. Jackson vetoed its re-charter because he felt it unethical.

Andrew Jackson changed how the president could operate. No longer the steward of the country at the helm of a government of the people, the president was now entitled (even obliged) to shape policy as he saw fit. He was to use his powers to bully government to do his bidding.

Thankfully this point of view hasn’t been abused (ahem, signing statements).

In the end, Jackson killed the Second Bank of the United States. It made a big mess.

He left that for his successor, Martin Van Buren, to clean up.

Recent Comments