Feeding Snarky on Language and Art

All written language is visual communication. This seemingly innocuous — even obvious — statement mystifies many who hear it. "I know from language," they say. "It’s verbal. It’s communicative. It’s certainly not visual." Of course, unless someone’s reading the sentences aloud to them, there’s noting verbal about the written word. It’s all ideograms in patterns we’re trained to recognize and manipulate.

And for the cartoonist — or any sequential artist, really — the number of ideograms they have to work with approaches the infinite. It’s what’s heartbreaking about "talking heads" comics, even when they’re great — yes, you can make your point or direct your story or tell your joke with the twenty-six letters of the standard English alphabet, with your figures standing, cut and pasted into four panels, barely showing dynamic motion or range. You can even be brilliant at it (two of my favorite webcomics in that vein are Her (Girl vs. Pig) and Lore Brand Comics). But as dry and witty and pleasant as these comics are, they do not take advantage of the richness of linguistic possibility in cartoon art.

Obviously, when considering "Romance and the Relationship" in webcomics, I’m drawn to those folks who do take such advantage, both in the traditional, glorious palette cartoons enjoy, and in the ways that webcomics break free from the traditional. And that focuses me, in entirely different ways, on Queen of Wands and No Stereotypes.

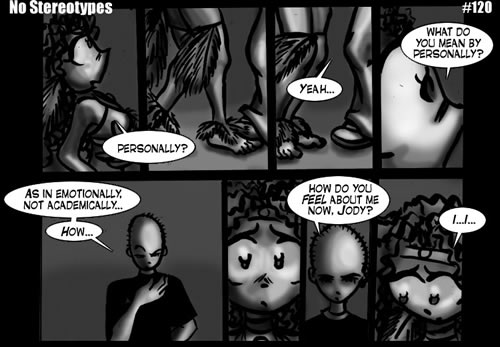

I would argue that one can’t truly explore romance in webcomics without communication, and Amber Greenlee has refined the art of communication in No Stereotypes (Heavy emphasis on ‘art’). The central relationship, around which all else revolves, is Jody and Atom, who are still very new to one another in many ways. You see this in the words they say, of course. All of Chapter Seventeen (subscription required) is entitled "Feelings," and the ways Jody and Atom, barricaded in the bookstore against the potential assault of Atom’s spurned ex Kat, slowly begin to reveal themselves to each other. Their words drive the conversation, of course, but they’re married to movements. Jody wraps her arms around herself — in part to cover her near-nakedness, and in part out of fear, only to lean forward, to reach out, to look up with those highly expressive oversized eyes. Atom shifts and turns, looks away, slumps his shoulders, then peers back through correspondingly narrowed eyes. In #140, Jody looks up, and says "you’re so… alone…." in a direct challenge, without being a direct threat. And Atom shrugs his shoulders and looks away, not disagreeing. All of which contrasts to their earlier conversation in Chapter Fourteen: Puppet Strings — a self-declared ‘argument’ — when Jody tries to convince Atom that his immortality is exciting and special, having potential impact on the world. Atom, far more confrontational than Jody then, cups Jody’s face in his hands. "What about the personal?" he asks. "How do you feel about me."

Jody’s body language tells us all we need to know. Leaning back, eyes even wider, suddenly very small and vulnerable, more overtly sexual yet clearly scared, Jody has been pushed too far, too fast. That’s never said, and after Atom lets go of her, never threatening yet clearly threatening, she feels his absence. She too is alone, which leads her to reach out to Atom in her own way. Slowly and carefully. The dance goes on, and their body language tells Greenlee’s story far better than the words alone would.

In contrast, though equally effective, is Queen of Wands. I’ve remarked before on Aerie’s ability to take the four panel strip and explode it to her purposes. In a way, she is a true realization of Scott McCloud’s theories of the web page as infinite canvas, made to match the medium rather than embrace the limitations of newspaper publishing. Where McCloud (and many of his disciples) are still using this infinite medium experimentally — more to explore how to tell stories than in telling stories, Aeire has taken the web’s canvas and used it to tell exactly the story she wants to tell, slightly oversized, four panels connected by a background pathway or lightning bolt, that leads the eye without interfering. And so Aerie’s strip, which is heavily conversational, has room to let the dialogue grow, until it reaches the levels of a play instead of a comic strip. Sentences traditionally compressed into the fewest words possible to fit inside word balloons can stretch their balloons to meet the needs of the sentence instead, and Aerie revels in it. Her artwork becomes snapshots — glimpses of figures in motion, caught and frozen, with only their words creating continuity.

The acme of this effect (yes, acme is a word, and was a word before Warner Brothers cartoons. No, it doesn’t mean "Company that provides robots and explosives at bargain prices") came in Kestrel’s coming to terms with her relationship with Seamus, what it was, and more importantly what it wasn’t. During a night of Karaoke, Kestrel and Angela discuss Seamus while he stands on the stage, singing. Aeire fades a picture of his singing self into the background. There but not obtrusive, making him the subject of the strip as well as the conversation, not disrupting the flow but influencing it, like a harmony line in the background. Kestrel talks about the nature of happiness, and how Seamus’s happiness in the end is what’s important to her. And we see him, happy, carefree, lost in song, their words wrapped around him.

Neither of these strips would have the same power in transcript form. Aerie’s sentences are allowed to grow, but always integrate into the art. The art gives them shape and purpose, and gives us a sense of something more than questions, declarations and interrogatives. Greenlee’s figures twist and turn and work with their hands and fold their arms and speak to one another without words, until the sentences they say become accent marks on the artwork. Both use the infinite language of art to expand their overall linguistics, and both are the richer for it.

In merging the visual with the textual, cartoons broaden what language is, and what it can mean. Whether broadening the visual palette a la No Stereotypes or extending and expanding the canvas to permit greater use of dialogue like Queen of Hearts, language means more than letters on a screen. And we’re the ones benefiting from the linguistics lesson.

Eric Alfred Burns is a writer and poet who comes from Maine and lives in New Hampshire. He has worked for Steve Jackson Games as a developer for In Nomine and has published articles, short stories and poetry hither and yon. He’s also the writer and developer of Websnark.com, proving he has far too much time on his hands. His one webcomic was terrible, and he has a cat.

Nicely done, Eric. I’m glad to see you in Comixpedia, and I look forward to the future of Feeding Snarky.

I was concerned when John B. announced the end of “Form is Function,” but Xerexes is clearly on top of things.

Thank you deeply.

And I appreciate the comparison to “Form is Function,” though please bear in mind that M. Barber didn’t suck, so there’s just so far we can go with it.