Mike Cavallaro's Parade (with Fireworks) is nominated for the Best Limited Series Eisner award for 2008. And while the award is for the two issue pamphlet version of the comic from Shadowline/Image, Cavallaro originally published the work online with the Act-i-Vate collective (you can still read it online and if you are worried about spoilers you might want to do that before continuing reading this column).

Cavallaro's comic immediately stuck out for me because of its animated art style and historical setting. In the front cover of the first issue, Cavallaro explains the origin of the comic as a mostly intact story told by a member of his family. The story starts with a flashback prologue wherein Paolo, the protagonist, briefly narrates his life up to the point where the main story occurs. He grew up on a large olive and orange farm owned by his family, survived fighting in the trenches in World War I, spent six months in America attempting to establish exportation business for the farm, and ended up back in Italy.

The main plot of the story spans a few weeks in 1923, centered on an altercation between Paolo and his socialist comrades and a group of local fascists. The fight ends in death and injury, and Paolo becomes a scapegoat who is tried and jailed for six months. By the end, his family is torn up, dead or alienated, and he starts anew with the farm, in the spring.

Cavallaro tells a story of personal struggle and tragedy, but he ends it on a high note: spring arrives, the world starts anew, Paolo will rebuild. Out of context one can leave the story confident. But a little historical knowledge leaves a number of open questions, and puts the events of the story in a more complicated light.

The historical setting of Parade (With Fireworks) is part of what kept me reading the serialization. The period of time between the world wars was one of great change and struggle, in Europe particularly. Perhaps my education is unusual, but I've seen/read/heard much more about the period in France, Spain, or Germany and very little on Italy (with the exception of Italo Calvino's first novel Path to the Spider's Nest which deals with the Italian Resistance during World War II). Cavallaro's story is set primarily in 1923, the first full year of Mussolini and his National Fascist Party's control of the country. I had to look this up when I was planning this column, because Cavallaro leaves a lot of this contextual information out.

At the heart of the story is an ideological brawl between Paolo and his socialist comrades and a group of local fascist thugs. Later in the story the fascist political power is brought to bear on Paolo's trial. This ideological struggle is shorn of most context in the comic, and I wonder what most readers will make of it. I would have liked to see more contextualization of this struggle in its relation to Paolo and Italy.

The onward march of history also leaves many questions for the nominally happy ending for Paolo. A brief textual epilogue notes that Paolo's conviction was overturned after the fall of the Fascist Party, but it leaves open the question of the twenty intervening years where the fascists increased their power and violence. I don't expect the story to expand to account for all this, but certainly a narrated epilogue, similar to the prologue might have helped flesh out the story and provide some needed context.

Issues of fascism and collaboration become apparent when one considers Paolo's sister. She is married to a fascist police officer and convinces him to get Paolo, who goes into hiding after the altercation, arrested. Her actions are couched in a certain naivety about the consequences, but, given more context, talk to the general issue of "normal" people's naive complicity in the power of the fascists.

In his introduction, Cavallaro notes the theme: "What tune are we going to march to?" This speaks to his intentions, though I'm not clear on how well this theme is evoqued. A closer examination of the sister and her role in this story might have better addressed the possibilities of this theme. As it is, we see no choices being made about the "marching" other than, very briefly, the sister. Those concerns aside, I understand Cavallaro's attempt, as noted in his introduction, to recreate a sense of his family member's storytelling. All that context would be assumed knowledge to the family audience. I wonder though if Cavallaro doesn't do his story a disservice by omitting these details for the reader.

The style of Cavallaro's images are fairly slick and reminiscent of animation. The fluidity and simplicity of the line give the figures a sense of motion. The mostly flat colors are supplemented by kind of transparent black overlay that adds shadow and depth to the images. The palette is primarily subdued earthy tones used in a realist way, but Cavallaro makes great use of varying his colors at key points, often with bright unnatural tones. The main altercation in the story, involves a small marching band and it's choice of sides between the socialists and fascists. When the band starts up playing the "The Red Flag", Cavallaro shows them in bright reds and oranges with dark purple linework, abstracting the background into an expressive and dynamic composition. Red also makes prominent appearance in a large image of the red soviet flag.

The use of red here, associated with the socialists, is, two pages later, used to display one of the fascist's anger. In an unusually colored sequence, Cavallaro splits a single image into two panels. One fascist is taunting and insulting the socialists. The top panel showing most of his head and mouth is colored in monochromatic red, while the bottom panel is colored realistically. This creates a striking sense of the man's anger.

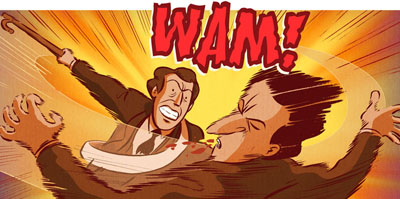

This use of red for affect is continued in a panel where one of Paolo's friends hits that same fascist with a cane…

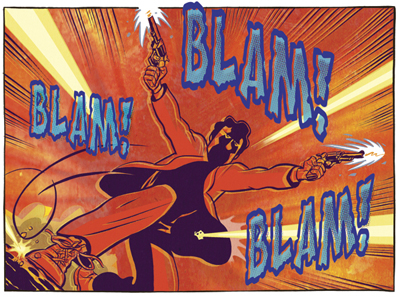

…and later when Paolo shoots at the fascists. The action-hero look of this panel is one place where I think Cavallaro missteps stylistically. A few of the panels during this violent altercation take on a kind of superhero style appearance that plays poorly against the otherwise realist nature of the story.

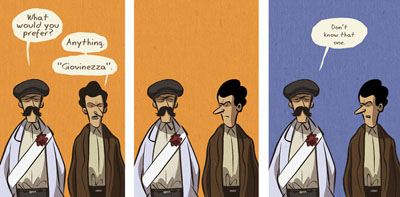

The use of red makes a visual connection between the socialists and violence, which is admittedly due to the socialist use of red as a metaphor for the blood of the workers. The way Cavallaro makes use of the red so prominently, makes this connection much clearer. The socialism and the violence are inextricably linked, offering a number of possible readings, none of which might be considered the correct reading or the even the one most motivated by Cavallaro. One might read the violence as a result of the socialists, that is, the red of their music is what starts the violence, a provocation to the fascists (the band could have played a politically neutral song and avoided the conflict). One could also read this as a kind of victimization, with the socialists targeted by the fascists, which precipitates the violence. But one can't ignore the fact that the socialists throw the first punch, so to speak. The bold reds are not the only case where color affects the reading of the images. Subtle shifts in abstract backgrounds adds to the reading of the images. Note the slight change of mood in the image below when the shift to blue adds an icy coolness to the band maestro's response.

In the end, Parade (With Fireworks) is a successful but slightly flawed work. The images are visually dynamic and the story is novel: it's worth reading. As for it's chances in the Eisner's, I can't say. I've not read any of the other nominees in the Limited Series category.

* * *

Taking a quick look at the "Best Digital Comics" nominees, I'm surprised I haven't heard any buzz on The Abominable Charles Christopher. It is an odd and rambling series about a indescribable creature and a bunch of animals living in the woods. It seems to be slowing building a longer plot amidst one-off gag strips and character studies. The monochromatic art is beautiful. Check it out.

Recent Comments