John Allison’s Scary Go Round is an odd strip. This is probably an obvious comment, but it’s a true one. Although when I say the comic is odd, I am not just talking about the fact that the strip has goblins, schools committed to the black arts, and the Portugese Man-O-War. I mean that the strip doesn’t actually fit into any of the useful boxes that critics keep around to do their work for them. It is not a hugely funny strip, although it is perhaps good for a wry smile. It is not a highly dramatic strip. It is not some heavily intellectual exploration of the comic form. Where a drama hits in the heart (Whether to break it, make it race, or whatever), comedy in the gut, and intellectual strips in the head, ultimately Scary Go Round hits in the eyebrow. The response to Scary Go Round is the raised eyebrow — the bafflement at the world of Tackleford. It is a strip that makes you go "Huh."

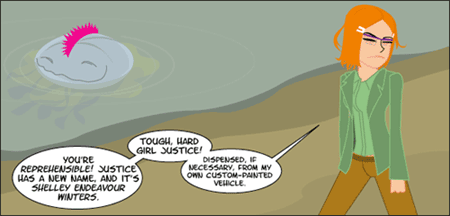

This is an approach that could backfire easily — deciding to make your comic strange is a dodgy proposition at best, as dozens of fallen strips can attest. But there are many flavors of bafflement, most of which Scary Go Round is decisively not. Most emphatically, it is not zany or wacky — Shelley’s adventures are strange, but demonstrate a restraint — an almost stereotypical British calm. There is none of the manic energy of, say, Checkerboard Nightmare or Superosity. When, in a recent strip, she is concerned about being killed and eaten by a witch, her comment is, "her fingers were like five lobster legs feeling me up for the farmer’s market," delivered with little more than a roll of the eyes.

The strange verbal tone evokes other comics that work o a sense of odd language – Achewood for instance — but even those fall short. Whereas Achewood is ultimately about its own language and strangeness, providing a sort of endless riff on itself, Scary Go Round has a contained directness — a simplicity, if you will. It is not purely about its verbal play. Rather, its banter is always about an equally vibrant sense of story. Ignoring the banter, the strip would have to be taken as a horror strip, full of weird and strange happenings. But in fact, more often than not often what is most strange is not the events, but the understated reactions to them. And, indeed, the strip seems at its strongest when it is understatedly weird, as opposed to in more explicitly strange storylines such as "Crock o’ Gold" which are, though certainly not bad, at least somewhat more typical. Sure, this strip, in which a bunch of goblins handing a cuckolded cuckoo a Groucho mask and saying, "Put this on, change your name, leave town" as advice is funny, but it’s nowhere near the sheer and creepy weirdness of the start of the next chapter. Truth be told, the "Crock o’ Gold" bit feels like a fairly normal humor comic. Whereas "The Child," in fact, this is generally true of the strip — it is strangest when it underplays its hand, and at its most normal when it trends towards the merely zany.

Let’s talk, then, about "The Child," which I think is one of the high points of the strip’s archive. The storyline opens with what is easily one of the creepiest single strips ever. But whereas the strip seems to gesture towards an exploration of what the child’s ominous message means, in actuality the strip goes nowhere near that — the rest of the storyline is consumed with the town of Tackleford responding to and ultimately panicking about the Child’s message. That the child is creepy is almost an incidental point — it is the content of his message that the town finds so alarming. Ironically, however, in the strip in which the message is given, the content of the message is the least alarming thing– in fact, it stands in a marked and strange contrast with the rest of the strip. Simply put, what’s creepy about the strip is the child himself — the strangeness of his appearance, the skulking walk he displays in the third panel, and his mysterious and black-haired master (Or mistress, as the case may be — we never find out). The child’s message is understated and virtually contentless, directing all of our attention to the child’s appearance. But it is specifically the message that consumes the rest of the story.

Let’s talk, then, about "The Child," which I think is one of the high points of the strip’s archive. The storyline opens with what is easily one of the creepiest single strips ever. But whereas the strip seems to gesture towards an exploration of what the child’s ominous message means, in actuality the strip goes nowhere near that — the rest of the storyline is consumed with the town of Tackleford responding to and ultimately panicking about the Child’s message. That the child is creepy is almost an incidental point — it is the content of his message that the town finds so alarming. Ironically, however, in the strip in which the message is given, the content of the message is the least alarming thing– in fact, it stands in a marked and strange contrast with the rest of the strip. Simply put, what’s creepy about the strip is the child himself — the strangeness of his appearance, the skulking walk he displays in the third panel, and his mysterious and black-haired master (Or mistress, as the case may be — we never find out). The child’s message is understated and virtually contentless, directing all of our attention to the child’s appearance. But it is specifically the message that consumes the rest of the story.

This kind of effect does not work well on its own. Scary Go Round would be a relatively unsatisfying strip to read, I suspect, were it the only strip someone read. It is too idiosyncratic, and the small and bemused response it produces is too underwhelming. Where Scary Go Round shines is in a sea of webcomics — on one tab out of twelve, read in between others. For my part, I read it after Something Positive and before Wigu — it makes a nice transition from Something Positive‘s active humor to Wigu‘s over the top trip through the bizarre.

I would be remiss in talking about Scary Go Round if I did not discuss the art. For all, but two storylines of the comic, Allison has drawn his characters on the computer, using a vector-based method that leads to an unusually angular look. The result is a world that is at once sparse and iconic. The world of Scary Go Round is one of solid, well-defined shapes — clean and uncluttered. In some ways, this contrasts the strip itself, which is anything but clean and uncluttered. But it works to make the comic look less than real. It adds a third note into the play that is the strip — one that contrasts with both of the others. The color pallet and abstracted look does not mesh with the darker horror content. But its abstraction also sets it apart from the casual banter, which usually draws its humor from an odd specificity.

Of course, fairly recently Allison changed to a hand-drawn style in a fairly high-profile move, and then changed back in an equally high-profile move. What’s interesting about this switch is that the new art style, which was very much the opposite of the old one, worked just as well at complementing both elements of the strip. Where the computer-drawn strips are clean and abstract, the hand-drawn ones are messier and more cluttered — not in a bad way that indicates a lack of composition, but in a dynamic way. And whereas the computer strips frequently made angles and lines off kilter or out of proportion, the hand-drawn ones were much straighter and more adjusted. (Compare the empty and unevenly shaped shelving in the first panel to the comparitive cleanliness of the mailroom.) The hand drawn strips also added more detail — the neckties on the school uniforms, for instance, became black and red striped instead of straight red. But the art remained in contrast to the clean rhythms of the banter, and the bright color palette remained, standing in contrast with the horror content.

Which is, when you think about it, quite an accomplishment — to have such a delicate balance survive two totally different art styles. An odd accomplishment, to be sure, but, well, like I said. Scary Go Round is an odd strip.

Recent Comments