Occasionally on the various webcomic related forums around and about, someone will ask "does a webcomic have to be funny?". The answer is, of course, "no."

Except… there's something wrong with that answer. Or perhaps it's the question. People already know serious comics work. Even if they've never seen one online, they know about the mainstream superhero romps at their newsagents. Why do they even ask? Why are they paranoid about doing a serious webcomic?

It's possible their subconscious are picking up on something they can't quite see themselves.

There is a vital quality of comics that makes the readers want to come back for the next installment. In funny comics, this quality is easy to see. It manifests as the gag and we can all recognize a joke. We know how they work and how they're put together. The structure of humor is wired into our social instincts somewhere. It's like working with clay – anyone can do it.

Now, remove the gag…

What makes the readers come back to a serious comic is much harder to see. This is more like working with 3D modeling software than clay. It's less intuitive and harder to fathom how it works. Still, although it's harder for the beginner, many people who are practiced with clay find changing over quite easy, since the underlying principles are the same.

And they are.

What makes a serious comic work is exactly what makes a gag comic work.

Dramatic Structure

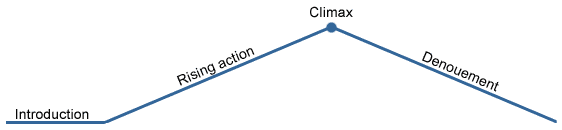

Let's start at the beginning. Anyone who's done a creative writing course, will recognize this.

It's a graph of dramatic structure. Here, it's intended to describe a plot, which is a long-term quality of a story. Moving from left to right, you introduce the characters and setting. Then a conflict arises and the action rises all the way to the climax, where the conflict is resolved. Finally, the story ties up the loose ends and delivers the happily ever after.

But it has other, shorter term uses as well and can be used to describe a single strip or a single issue. Do so, and this becomes the recipe for how you make the readers want to come back next time – whether you're writing a gag comic or a serious one, whether a page a day or an issue a month.

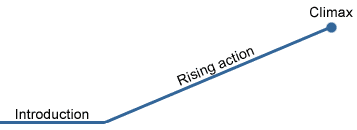

We just need to make a small edit…

Mainstream Comics

The multi-issue story arcs in superhero comics use the dramatic structure just as any story does, but they also use the cropped version above over the course a single issue in that arc in order to entice the readers back next month. The comic will start where they left off last time and slowly raise the tension, the action and the stakes over the course of the twenty or thirty pages, before hitting you with a climax.

At which point, it stops – either just before or just after the climax. Either way creates drama, usually in the form of a cliff hanger. The readers are then much more likely to come back next month to find out what happens next, at which point there may or may not be a slight dip to resolve the previous climax but either way, the action will continue to rise further.

A lot of webcomics use the same idea. For example, this page is the climax of chapter 7 of Gunnerkrigg Court by Tom Siddell. The very next page is the last in the chapter, creating a cliff hanger. Tune in next time…

Of course, because it cannot be entirely avoided, you occasionally get a denouement when the story arc ends, but it's interesting how many story arcs end on a hint that it's not quite over yet. There's always a touch of an unresolved climax hanging on the end to make sure you keep on reading.

Stopping either side of a climax is a really great way to drag the readers back next time but mainstream comics have thirty pages to play with in the meantime. Webcomics, on the other hand, update a page every day at absolute best and frequently update as little as once a week. Like the print comic, they need to drag you back for next time – except that the webcomic has to do it every single page.

How? Same way.

Gag Comics

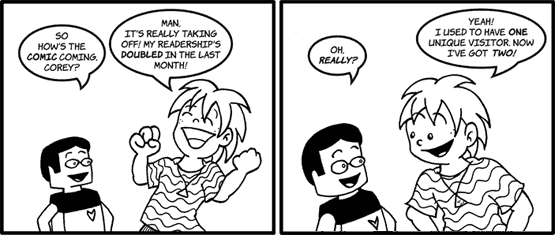

Let's examine the dramatic structure against some gag comics. Gag comics use this same dramatic structure automatically without realizing it, because that's how a joke is put together. Here's an example gag comic from Cortland by Matt Johnson…

And here's how it breaks down using that same dramatic structure.

| Introduction: | "How's the comic coming, Corey?" |

| Rising action: | "Man, it's really taking off! My readership's doubled in the last month!" "Oh, really?" |

| Climax (or punchline): | "Yeah, I used to have one unique visitor. Now I've got two!" |

A gag comic has the same dramatic structure as a complete story. In fact, any sort of joke does. There's usually no denouement, though, although there can be.

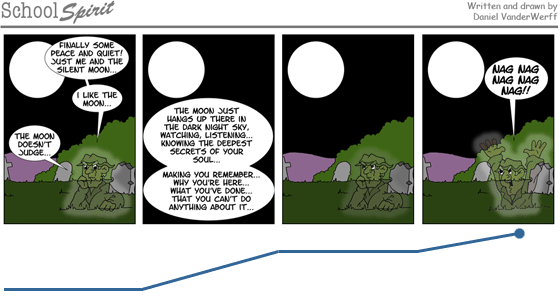

Let's look at a couple more. This time, I'll graph them directly. Firstly, here's a single strip from School Spirit by Daniel VanderWerff.

It has the same structure again, except this time there's a pause for comic timing. In terms of the graph, it holds the tension for a few seconds before we get to the punchline.

This is a strip from Zoology by Nathan Birch.

It's a little more complex, as we have a change of scene. We introduce the subject of the strip in the first panel and build some drama in the second. Then we switch scenes, introduce the new character, and he lends some more drama to the strip in the fourth panel. The two lines converge for the punchline in the last panel. However, in spite of the extra complexity, you can still see it follows the same pattern.

This is the exact same technique as used by the mainstream superhero comics. At the end of every update (whether a strip or issue), you have a moment of drama balanced on a climax. It doesn't matter if it's big, small, funny or serious. It works the same way and for the same reasons.

And it's what a lot of serious webcomics don't have.

Serious Webcomics

Using this dramatic structure to create cliffhangers, drama and gags happens automatically. It's a natural part of writing that we've picked up subconsciously by reading stories and comics.

And yet serious webcomics have a big problem with this. Mainstream comics entice you back every month and gag comics entice you back every day. It just happens and we barely have to think about it. Serious webcomics, however, generally do neither.

What, exactly, is wrong here?

The problem is that many writers of serious webcomics use comic books as a guide – which is to say, they have a cliff hanger around every thirty pages or so. Unfortunately, they also use webcomics as a guide and release pages singly. Most of those pages, however, probably don't have anything much to grab the reader.

A quick bit of math shows the problem clearly. A mainstream comic is released once a month and will have one cliff hanger at the end to bring you back next month. A serious webcomic using the same pacing but updating, say, once a week, would have a cliff hanger once every twenty weeks or so. That's just twice a year that the comic grabs you and screams "Man, you just gotta come back next time!"

It's the worst of both worlds.

The serious webcomics that do it right – that grab you at the end of each and every comic – are usually the gag comics which have briefly gone into serious mode because something important is happening. General Protection Fault and College Roomies From Hell are two popular comics that regularly do this. They abandon the gag-a-day mentality and give you a drama-a-day comic. Because they're usually gag comics, they're used to keeping a little climax at the end of every strip and this carries over when things get serious.

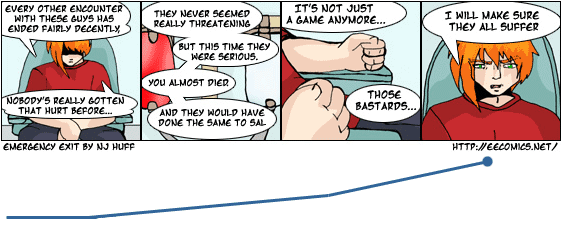

Here's an example of just that. Emergency Exit by NJ Huff is a humor comic going into serious territory. Yet, even without a punchline, our graph maps the same way.

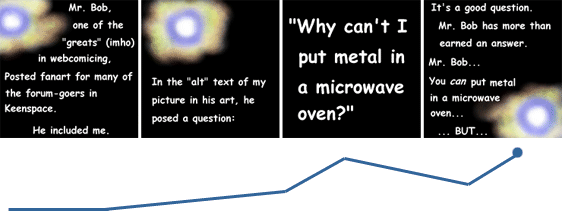

The same dramatic structure rules again, only instead of over thirty pages, like a comic book would do, this is in a scant few panels. Nevertheless, the cliff hanger is there and the reader will want to know what happens next. Even the rare non-fiction comic uses the same tricks, such as this example from the science comic Reasoned Cognition by Ryan Kolter.

If you're creating issues akin to comic books but releasing the pages singly like webcomics, there are a lot of pages which either have very little drama or none at all. It's too large to include directly, but here's an example of a page from The Curious Adventures of Aldus Maycombe by Janine Harper.

Our graph is a flat line. Nothing much is happening, there's no drama and no cliff hanger. If the next update of this webcomic is in a week's time, most people would have forgotten this page entirely and may have to struggle for a moment to recall the context.

However, flat lines do have their uses. With the amount of action so small in a single page or strip of a webcomic, you can also hold the level of action from the previous comic. Here's a good cliff hanger from Tales of Pylea by A. Chow and Matt Summers where big, dramatic things are clearly beginning to happen. This next comic resolves nothing but simply holds the level of drama. This works best with tension. You can have a single comic which neither dips nor rises, to maintain the tension set up by the previous comic and keep the readers' breath held.

There are a few serious webcomics such as Inverloch by Sarah Ellerton that release batches of pages instead of a page at a time. This is usually a compromise between the mainstream rate of twenty to thirty pages a month and the webcomic rate of a page at a time. Usually, it's not a whole "issue" but having a few pages even without a cliff hanger gives the reader more context and progression than a single page at a time.

Keeping people coming back

Using this dramatic structure to create gags, dramatics and cliffhangers keeps the level of interest high, motivating the audience to keep coming back. It also helps them remember what's going on since the more interesting something is, the quicker and easier it will be to bring it to mind.

And it's not just comics. Movies, television, novels, computer games… They all use this short-term structure to create moments of drama and to keep your interest peaked. This article did the same, leaving little cliffhangers at the end of some of the sections. It's a natural part of writing and happens, most of the time, completely automatically.

But with serious online comics, people tend to follow the wrong parts of two separate models, trying to write a mainstream comic which is released in pages like a webcomic. And it does work, for the most part, usually because of high quality of the writing since it is the true storytellers who generally want to write serious comics. Nevertheless, there is an advantage that they lose by not using this short-term dramatic structure to drag their readers back each time.

So, does a webcomic have to be funny?

No.

But…

Sorry, I came to this party late. You folks have all been talking about redrawing/writing your early comics and approaching things from a prototype angle. Interesting.

Xerxes made a comment about flawed comics. How would you tell if your comic was flawed? What sorts of things tell you that the comic is going in the wrong direction for the audience you have (or maybe hope to build?) It seems like you can adjust the protoype as soon as you see a problem.

Obviously, if your visitors drop to zero or you start getting vicious hate mail…what else would you watch for?

Flawed is ultimately a subjective term, but in some cases it's not going to be a very controversial opinion. Think of a webcomic with great writing but horrible (and not horrible in an intentional way but just bad) art. Conceivably it could be rescued with another artist redrawing the work. (This could easily work the other way where an artist is amazing, but has no talent for the "writing" side of making comics)

Or what about a comic with a storyline but one that the author largely botched in the beginning only getting tone, pace and plotlines together at mid-way (not an infrequent event for a webcomic). Do you leave it as is or potentially polish a gem by fixing the front end?

I wasn't thinking of audience numbers. If that's a really explicit goal for the creator though then that opens up it's own issues/questions. Sometimes you need to stick with a project to build a big audience – but some projects will never catch on – how do you know which is which?

____

Xaviar Xerexes

Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Gnaw.

I've been reading webcomics since 2004 and my first webcomic was RPG World. It is a serious and funny comic that kept me attached to the screen.

That doesn't mean serious webcomics cannot have funny things in it while reading! My webcomic is humorous that is a series that keeps on continuing but there's its serious moments!

Webcomics with storylines keep me coming for more to see what will happen? Sometimes, if the story is really good, it makes the reader forget about a moment in the past that all for a sudden it will appear without people noticing is very good!

To me story/serious webcomics > gag/random comics

I realise it doesn't read quite like that, but that's intended to be the main point. The article does rather come down on the daily update side rather than multiple page updates, though. That was a mistake. Either addresses the problem.

It kinda is, actually.

I should clarify: it's the only way to measure sucess on the web, which makes it the same in the minds of many. It's a bit like money. No, money doesn't mean you'll be happy or famous but it's a very convenient measure for sucess and the only one that matters for most people because of it.

I like that article, too derikb. There's a point in there I wish I'd thought of so I could have addressed it. *snaps fingers theatrically*

– Joel Fagin

Jonathon Dalton [url=http://www.jonathondalton.com/mycomics.html]A Mad Tea-Party[/url]

The web makes a mighty fine place to prototype long-form comics. Although, it's far from the most ideal way to read a graphic novel in 3 pages-a-week installments – it will build an audiance that wouldn't exist otherwise.

Granted, this prototype audiance is often different than the audiance who would buy the book, it's a great motivator as you drive through your work.

The web is the "DVD extras" of graphic novels. It's watching something big being made real time. There are a lot of process junkies out there, like me, who this appeals to. So, really, the "product" is quite different than a gag-comic. The two really shouldn't be compared when measuring success.

I've had two years of reader-motivation pushing me along to finish my book. This is how I measure success.

Steve "Fabricari" Harrison

That is similar to an idea, I've nursed along but never really written much about which is how some creators use the web as much like "school" as they do a final published piece.

In that case, many of those creators should be spending more time and effort on revising and re-presenting their work when it's done (however they want to parcel it out on the web). There are many webcomics that show promise yet are flawed in some way – either consistently or more commonly in mistakes made at the beginning of the work. These "first drafts" really could be significantly improved if revisited and the exposure on the web can be part of that process. But I'm not sure how many creators take the time to go through that process of revision after throwing it out on the web.

____

Xaviar Xerexes

Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Gnaw.

I was given advice, early on, from Sergio Aragones, that was quite different. He basically admonished me against redrawing pages. An artist can spend their lives redrawing a book over and over, because that artist is always getting better.

No, I believe it's better to finish the book. Learn from it, and do another; do it better.

What you're witnessing when you see a graphic novel go from crap to polished pages is the growth of an artist. This is mostly noticable with amateurs (like myself). I doubt you will see such stark transition in my next book, as I've become more rutted into a method. You see more of this in the first volume of Megatokyo, but it's non-existant in the subsequent books.

The exception is when publishing for a company paying you for your work. If you have an experienced editor advising you to make changes pre-press, well, you do that. And a lot of times, the editor will scrutinize for things that you don't see. They might be more concerned about story-telling flaws than art flaws. But, if you're doing this as a hobby (let's not start a debate on the semantics of "hobby"), it's just better to create more pages. Don't toil on the past. You've learned so much more since those early pages.

And when you redraw those early pages, you're robbing yourself of your time.

Yes, I realize there are people who have reworked their earlier pages, and have done it successfully. I just think, in that time, they could've worked on something fresher, better.

"You have 3000 bad pages in you." – Dave Sim

Steve "Fabricari" Harrison

I think we're pretty close here actually. Maybe? 🙂

What I was saying was something like – there are many (more than a few for sure) webcomics that sputtered in terms of audience – let alone getting published – b/c they were flawed, not b/c they were ultimately bad. If it's a story worth telling I think more folks ought to consider getting and taking the feedback of the web, and looking at whether a project is worth revising.

(Also for what it's worth – 3 out of the 4 first time graphic novelists on the SPX panel said they had redrawn parts of the books' beginnings after finishing)

____

Xaviar Xerexes

Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Gnaw.

Well I dont know If My comic falls into the "Funny" or "Serious" webcomic style, for the most part when I put it together, I will either switch between seriousness or jokes but that depends on how I think the characters are behaving. Still I cant complain about my readership or the numbers in my traffic, since I am consistantly between the High 80’s to Low 100′ on the webcomics list. Then again It could just be the porn. A Call to Destiny an Adult Sci-Fi webcomic.

But I'm not sure how many creators take the time to go through that process of revision after throwing it out on the web.

I do it pretty often, actually, but I am Jack Shepherd level OCD.

Tim Demeter

does a buch of neato stuff.

GraphicSmash

Clickwheel

Reckless Life

"If it's a story worth telling I think more folks ought to consider getting and taking the feedback of the web, and looking at whether a project is worth revising."

I'll jump back and say that I totally agree about the value of honest feedback – it's a rare and precious thing. You can't pay for that kind of learning.

And while I'm adverse to major rewrites – I do think that polishing up a script or "fixing" some art here and there is completely acceptible.

I must admit a certain passion for this topic of rewrite now: I'm mere pages away from finishing what was ultimately a prequel to the book I drew 10 years ago. (WHO'S LUCAS NOW?) Now I'm faced with either reposting old and crappy art, redrawing it, or forgetting it. I'm leaning towards forgetting it (it's that bad) or archiving it as an "extra", and starting a completely new story.

Steve "Fabricari" Harrison

Jonathon Dalton [url=http://www.jonathondalton.com/mycomics.html]A Mad Tea-Party[/url]

Less then a decade…

I'd hope so! Of course, 2 of the 4 panelists on the First Time Graphic Novelists Panel at SPX said it took them 7-8 years of off and on work to finish their first GNs.

____

Xaviar Xerexes

Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Gnaw.

"3 out of the 4 first time graphic novelists on the SPX panel said they had redrawn parts of the books' beginnings after finishing"

and then…

"Of course, 2 of the 4 panelists on the First Time Graphic Novelists Panel at SPX said it took them 7-8 years of off and on work to finish their first GNs."

Methinks I see a pattern. Pardon me while I LOL a bit.

Steve "Fabricari" Harrison

One of my professors in creative writing school, a poet, told me, “No great poem is ever finished. It is only abandoned.” For an extreme example: Walt Whitman rewrote (and republished) “Leaves of Grass” many times over the course of his lifetime. Pain in the ass for literary professors.

Joey

http://www.webcomicsnation.com