In one of my previous articles for Comixpedia I spoke of the hierarchic structuring of the comic industry and alternative viewpoints to democratize those hierarchies. I asserted that change cannot flow top-down from corporations controlling the industry or from technological innovation, but rather from a reorientation about the conceptions of the medium. This piece explores one way that we as individuals can potentially alter the perception and organization associated with this medium: through vocabulary. People associate with the world greatly through the words they use, and different expressions can largely determine the way in which they relate to concepts. Thus, by reframing the vocabulary associated to "comics" we can alter the perceptions and considerations that they create in our culture. This issue is by no means new to comics, though the approach taken here will develop a deeper and more expansive solution than those proposed in the past.

Framing the Issue

In his recent books, Moral Politics and Don't Think of an Elephant, linguist George Lakoff discusses how language contributes to peoples' political understandings. For instance, he points out that a term like "tax relief" inherently connotes that taxes are somehow burdensome and thereby negative. So long as this term is used in discussion of the topic, it implicitly frames all debate in ways that are favorable to those against taxes—usually conservatives. In response to this, he advocates changing the debate to talk about "tax investments" to heighten the beneficial aspects of taxes, like the fact that they give back to the community by helping to pay for things like infrastructure, education, fire and police departments, etc. Indeed, if the government does not have enough money to pay for those things, they become ceded to corporations and lost from the ownership of the citizens. By paying taxes, citizens contribute to the common good, making them a patriotic and essential part of living in a democracy.

Lakoff asserts that vocabulary both contributes to and draws from underlying cognitive "schemas" in the mind. These can be thought of as conceptual networks oriented towards a particular categorization of the world. Thus, whenever certain terms are used, they activate certain broader understandings in the mind, and continual usage of them solidifies the preference for one framework over another.

While the vocabulary used in the comic industry has not necessarily been manufactured by think tanks in the same way political terms have, it still plays a critical role in defining the way people relate to and treat the medium. Thus, one way to incite progress towards a better perception and treatment of the medium is to effectively change our vocabulary, which thereby changes the overall cognitive frame in which the material is engaged.

This sort of movement has been undertaken successfully before, outside the context of partisanship, most notably with regards to gender equality. Terms such as "stewardess" and "chairman" are commonly replaced by "flight attendant" and "chairperson," as has the prevalent alteration of pronoun usage to gender neutral or equal forms such as "they" or "him/her." With a concerted effort, making similar changes for "comics" should not be an impossible feat.

So, what's so bad about the vocabulary of comics as it is? Let us now turn to examine various pernicious terms that subtly pervade our industry and culture.

Words, words, words

At the forefront of this problem is the word comics itself. In addition to the general belief that they are for children, the word suggests that the objects are somehow funny or comical. According to historian Roger Sabin, evidence for the origin of the term lies in humorous prints sold at public events in the 1700, which were known as "comicals" and abbreviated sometimes to "the comics."

This framing might just be an English problem though, since in other countries what we call "comics" conjure up entirely different meanings. For instance, in Italian Fumetti means "little clouds of smoke" – referring to the shapes of speech balloons and in French, Bande Dessinée means "drawn strip." Meanwhile, the Chinese characters used in manga consist of man – "involuntary, in spite of oneself, corrupt" and ga – "pictures." Each of these languages brings a certain framing to their terms. Though their effects might not be overt, the general orientation to them has ramifications on the general categorization of the issues.

The problems extending out from "comics" leads right into its uses as an adjective. The intrinsic implication of comedy should be obvious since comic strips is synonymous with "the funnies" for many people.

More problematic issues arise with regard for format, as in comic book. The main concern here is that they aren't usually books at all, but magazines (or conceivably, pamphlets). This has caused the term "book" to be unusable by formats that legitimately deserve the title. In colloquial usage, related back to the humorous connotations, the term "comic book" has been extended to mean a simplification of something, or a watered down, simplistic, intellectually void, and immature thing.

Degrading implications also emerge in the terms cartoon and cartoonist, which associate the drawing style with abstract and "funny" images. The term originally derived from an Italian word for the preparatory sketches done on pasteboard for paintings and other art works. However, like "comics," following the 1843 publication of the British Magazine Punch, it began to designate graphic satire and humorous drawings.

"Cartoon" also poses problems for the natural association to animated movies, which are also referred to as "cartoons." Again, the biggest problem with this is that it then leads toward the connotations of being aimed at children, despite the massive numbers of adults who watch animated movies and TV shows.

The poor framing of comic book has led to the now popular term graphic novel, which by many standards aren't actually novels. Rather, they are books – of which "novels" would be a specific subset. While this may not seem to be a serious issue, at the very least "novel" connotes fiction, which leaves out non-fiction works such as Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics and Tsai Chi Chung's philosophy series, among others. If the word "book" had not been culled by "comic book," it could have been used here, and this dissonance between fiction and non-fiction would not arise. Indeed, as its popularity rises, "graphic novel" is growing to include trade paperbacks and illustrated books as well, simply because of the nouveau marketability of the term.

Relatedly, issues arise in the identification of the "medium" as well. Comic medium or comic form implies that the structure of sequential images interacting with or without text is identified inseparably with the social object we call "comics." This subverts the potential of the here-undefined "medium" as being attached to the social stereotypes connoted by "comics." The same is true of using "comics" as a term for the medium – such as McCloud does – and perhaps is even more subversive, because it doesn't even allow for a separation at all. What McCloud really tries to promote (among other things) is the idea of the comics medium as a language, though he tries to do it by redefining comics to be that language. By maintaining the term "comic medium," it places the dominant focus on "comics," making the notion of the "medium" dependent on it.

Similar problems arise with Will Eisner's term sequential art (or the proposed shortened version "sequart"). Again the phrase does not explicitly define what the medium is, banking on the culturally fuzzy and subjectively defined "art," which itself is bound to social not structural implications. Of course, this was partially why Eisner created it, as linking the structure to "art" could potentially gain it some respectability in contrast to the inherently soiled "comics."

Additional troubles arise in the implications given to those producing these works. For instance, writer-artist implies that the separation of these two jobs is the norm, rather than having an individual who "writes in pictures." (Many authors including Osamu Tezuka and Will Eisner have expressed that this is more accurately the way they think of the process.) Notice this in contrast to the commonly used manufacturing terms: writer, penciler, inker, colorist, etc. Each of these terms accurately matches the acts of those they describe, though the fact that they are the norm further insinuates a division of labor in the making of any work.

Also oriented towards the business frame of mind is the term creator. While it may not seem harmful, it implicitly connotes a sense of property manufacturing and ownership as opposed to "a person who produces a piece of (visual) writing." This confines us to a frame in which those who produce this medium belong explicitly to a form of industry. It thereby carries a whole connotation of business and property, as opposed to authorship and expression.

Also exemplifying the insular and business focused aspects of comics is the term Direct Market. Developed over the past thirty years, the term refers to the system that sells comics and related merchandise on a non-returnable policy straight to the specialty comics retailers that had emerged out of the "underground" scene. The term on its own reflects the industry's emphasis on remaining turned toward those within the comics culture since the market sells direct to comic stores, as opposed to out bringing in non-comics culture readership.

A Frame of Mind

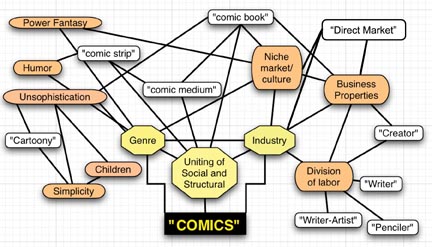

The network of concepts described above will be referred to as the "Comics-Frame", since its basic frame is: Sequential images are comics. As will be shown, identifying an acceptable root concept for the underlined portion of this formula will be key in reframing the understanding of this medium.

Based on the terms described, what sort of salient framework is created by the Comics-Frame? It views the medium and the product of it as inseparable. That conglomeration is in turn interpreted as inherently simplistic and humorous (and thus child-focused), manufactured by groups of individual "skilled" workers, and tied to a specific economically based print culture dominated by escapist fantasies or childish entertainment – mainly genres of superheroes and science fiction/fantasy.

Bearing this generated perspective in mind it is not surprising that creations not resembling this mold fight an uphill battle. Indeed, the corporations and businesses at the head of this industry would have no motivation for changing the perspective or the terms, because the current framework is oriented towards their product. They have a vested interest in the consideration of "comics" in one way as opposed to another because maintaining the status quo seems more "safe" in terms of a business model. By reframing the issues, new business models must work to accommodate those terms. This is already being seen, as the "graphic novel craze" has already led publishers and comic companies to match demands of "sophisticated comics" by supplying product along those lines (or to create demand through supply, in some cases). However, "graphic novels" have not become a substitute for the frame of "comics," but merely an upscale substitute.

This becomes very apparent in Eddie Campbell's recent "A Graphic Novelist's Manifesto," which states outright that GNs should be a movement that disowns the problems with the term and takes "the form of the comic book, which has become an embarrassment, and raise[s] it up to a more ambitious and meaningful level." While Campbell wants to let "comics" stand as a phrase to represent its associated concepts, "graphic novel" should strike out to form its own cultural conception. Many of these sentiments can be compatible to the aims of this work. However, this rallying cry does not ever directly address the issue of reframing the medium itself.

Solutions

The idea to change the term "comics" is hardly new, and is largely the reason why terms such as "graphic novel" or "sequential art" have emerged in the first place. Indeed, the accelerated sales of "graphic novels" and "manga" in recent years can most likely be traced to the fact that they are not called "comics." However, there are two main problems with these approaches. First, by only changing the terms for "comics," the larger systemic problems associated with them remain the same.

Changing to "graphic novel" only frees a subset of formats from the issues arising from the broader term "comics." It does little overtly to move away from the industry-line creative method as being the norm, or the maintenance of an industry over individuals, nor does it address the primary concern of what the medium is identified as (though it takes steps closer).

The second problem relates to this further: these terms do not reframe the deeper implications conjured up by the systemic network of terms associated to the frame of "comics." Shifting to the frame Sequential images are Art through "sequential art" (or literature through "graphic novel") maintains many of the same terms as the Comics-Frame, while opening up many more issues associated to it.

This is the same problem faced by the changing of "comics" to "comix." The intention was for the word to change from its previous comical meaning to one insinuating the co-mixing of words and images. Again though, this failed because it did not address the deeper frame based on the previous usage, with results similar to the changing of "women" to "womyn." To the masses it seemed like an odd insignificant change, while within a small cultural group it signified a particular subgroup (in these cases, "underground" comics and certain feminists respectively). They are even less effective because the change only occurs in written form; while spoken there is no distinguishable difference.

To successfully alter the way in which this medium is considered, we must change our vocabulary relating to it by appealing wholeheartedly to a different network of concepts. Changing vocabulary is not just a matter of coming up with new terms, but as Lakoff teaches, it is a matter of invoking an alternative perspective with which we can engage the issues.

Throughout my writings I have stressed that the "comic medium" of sequential images is actually a visual language (VL) which unites with textual language in the social objects of comics. Thus, "comics" does not refer to any sort of structural attribute (such as sequential images, or visual-verbal blending), but rather to the tangible objects, a social culture, and a community that has associated itself to this visual language. As a result, the term "visual language" itself reframes the issue of considering the medium, and can provide an alternative framework to the existing one that poses problems.

The biggest advantage of the "VL-Frame" is that people already have a predisposition for it. Most people have some sense that the creation of graphic images is in some way a language, whether or not the reasoning behind those feelings are theoretically accurate. This should come as no surprise, since those intuitions stem from the biological capacity that all people have for image making. The only reason a full acceptance of this intuition has not come to full fruition is that social terms such as "art" and "comics" have stood in the way of accurately identifying such a visual linguistic ability.

Thus, recasting the issue in the VL-Frame will not be the imposition of a new point of view unfamiliar to people. Rather, it is a matter of creating vocabulary that nurtures an understanding that people already have.

In deriving a new vocabulary we must bear in mind the pragmatism of the effort. The change cannot be overly radical or superficial ("comics" to "comix"), and must reflect a broader conception of the medium. In this case, that means replacing the entailment "sequential images are comics which are childish entertainment/superhero fare" framework with the view that "The ‘comics medium' is actually a Language." In fact, this becomes the first term that becomes restructured: a "comics medium" no longer exists, because it inherently invokes "comics." Rather, it simply becomes "visual language," and thus provides the core concept from which the further network of terms can follow.

Note also that simply saying the phrase "the language of comics" is also problematic in that it is ambiguous between two meanings. In the first, it means "the language that is used in comics"– essentially VL – and is comparable to saying "the language of novels." However, the second meaning implies that "comics is the language," similar to "the language of English," thereby upholding the Comics-Frame. In order to reframe the issue entirely, "comics" cannot remain in the actual phrasing of the medium.

Granted, some of the terms above are not all that pernicious, merely inaccurate. For instance, "graphic novel" retains an air of respectability and impartiality with regard to a notion of visual language, and can work perfectly fine in concert with the VL-Frame, despite its imprecise extension of "novel" for "book." Though it lacks the buzzwordy feel of "graphic novel," a more accurate phrase such as "graphic book" could accomplish much the same purpose, and appropriately extend to works of non-fiction as well, which GN has a clunky awkwardness doing. Of course, "graphic book" begins to encroach upon the feel of an "illustrated book" which again leads to children's reading. Perhaps another solution would be using "graphic" or "visual" as a general adjective, for "graphic fiction" and "graphic non-fiction."

Similarly, a term such as "writer-artist" does actually describe what those people do within the current frames of understanding, though it inherently implies that it is an exception to the rule of separating those jobs (not to mention invoking a certain frame with "art"). Using the common "author" in its stead would in many ways heighten the aspect of it being an individual creator, or if more uniqueness is needed, a "visual author." Moreso, works that have more than one person creating them can have an overt title of "co-authors" while inside the division of labor can be further divided. For instance, regarding my recent book We the People, I usually say that Thom Hartmann is the author, while I am the "visual co-author", since my job was to adapt his text with visual language.

Note that by focusing the creative aspects into a term like "visual author," we immediately invoke the VL-Frame. Automatically, the role becomes "one who produces a type of language," as opposed to "one who fills some sort of utilitarian role of production." It also stymies the humorous, potentially childish, and loaded connotations carried by "cartoonist." Furthermore, if "visual author" becomes the standard, then it reorients "authorship" to be the norm, pushing the industry-line model of division of labor as the exception. Simply by this one phrase, the entire structuring of perceptions related to the medium and industry becomes recast.

The same sort of effect can be gained by using the verb "write" to describe the process of creating sequential images, as opposed to "draw." "Draw" implies the creation of a static image, while "write" carries an overt connotation of it being a linguistic act. Visual language authors don't "draw comics," they "write their books in pictures."

Whatever types of new terms could be arrived at, these are the types of issues that must be dealt with in order to reframe the perception of this medium and the works that use it. They must effectively restructure the speakers to a different cognitive base with which they can relate to the visual language and its products.

The difficulty in establishing a new vocabulary to reframe these issues is the obvious: getting people to change the words they use. New language must both be effective and concise enough to accurately express the change in conception without seeming forced and it must be utilitarian enough for actual usage: they have to be terms that are readily intuitive and accessible. This means that our endeavor should not be to create new words (like "sequart"), but to redeploy existing terms into new uses appropriate to the frame we want to promote. There is nothing new about the words in "visual author," or "visual language" but by juxtaposing them, a new meaning is created out of the combination of the old ones. Of course, this is partially the key to it all—by drawing on existing words, those meanings can be redistributed to create another new conception. From here, we can work to create "new words" so long as they carry some sort of direction toward a preferable frame.

Language is a communal structure. Thus, rather than completely offer terms here, I invite those who are interested in creating new vocabulary to join together in a discussion at my forum (or on this page, below). In a sense, we can form our own "VL Think Tank" to agree upon new terms communally and discuss how change could be implemented on a wider scale.

One final caveat is in order. While the prospect of altering people's conceptions of this form might seem exciting and worth rushing headlong into, we must remember that enacting such a change on a broad scale will require time and some effort. At the very least, it demands enough effort to think about how you're saying something as you're saying it.

Indeed, while the establishment of a codified set of terms might be useful in engaging this issue, it is not absolutely necessary. As Lakoff advises, when discussing contentious issues with someone from a differing perspective, the main objective is to address their concerns by reframing the issues. This can be done without jargon, simply by reorienting the issues toward the VL-Frame instead of the Comics-Frame, and being sensitive to directly address the beliefs of your discussants.

While the invocation of the VL-Frame is the most important aspect to this vision, certain specific jargon can go a long way, especially since the term "comics" is so pervasive. So long as the current vocabulary remains in use, it will always implicitly reinforce the Comic-Frame. To be more direct: as long as they're called "comics" they will always limp along behind other culturally accepted media simply because of the network of concepts associated with that term.

This is not meant to be discouraging. Change is possible, it just requires the proper frame of mind to enact it.

Neil Cohn writes and researches about visual language, and is the visual co-author of the political book We the People: A Call to Take Back America, with Thom Hartmann.

If you’re going to be pedantic about terminology, please note that “trade paperback” doesn’t mean what you seem to be referring to. You wrote: ‘”graphic novel” is growing to include trade paperbacks and illustrated books as well,’ as if “trade paperback” were a category of content (presumably referring to a collected monthly serial). The term is actually a publishing format: a book with a paper cover, in a size other than the standard “mass market paperback”. Graphic novels can be – and are usually – published as “trade paperbacks”. Furthermore, many collections are graphic novels; they just happen to have been serialized first; Great Expectations or Tales of the City is no less a novel due to its initial serial publication. Using “trade paperback” to refer to “a collection of serial issues” is just as much a popular misnomer as “comic book”, and paints us further into the corner in terms of the language available to us to describe what we create and read. Plus, it’s simply incorrect. When you want to refer to a collection of a serial, try “collection” (or “collection of a serial” if it’s unclear from the context).

I think your dismissal of “creator” is idiosyncratic. I simply don’t see the connotations you allude to, associating it with property, manufacturing, and business. They certianly don’t exist in my own mind, nor do I see them in how other people use the term. “Creator” is most commonly used in reference to God, and whether you believe in such things or not, God’s relationship to what he created isn’t generally cast in terms of ownership or business, but rather in the sense of authorship or creativity. I have never heard “creator” used in reference to manufacturing; the prevailing terms there are “worker” or (no surprise) “manufacturer”. Proprietariness only comes into the picture with the term “creator-owned” and it’s the word “owned” which carries that baggage. It almost seems as if you are looking for justification to throw out every useful term in our current vocabulary, in favor of an All-New All-Different Giant-Sized LeXicon.

You wrote, ‘The biggest advantage of the “VL-Frame” is that people already have a predisposition for it,’ but the biggest irony of this statement is that most people won’t have the slightest idea of what a “VL-Frame” is (even if spelled out as “visual language frame”). If you want this terminology to actually catch on, I strongly suggest talking about it in a language that {ahem} we the people use. I understood it, but I can (usually) understand William F. Buckley’s prose as well, which places me in a minority. This type of language isn’t used much of anywhere outside of academia, and it’s been my experience in my two decades within the ivory towers that even here, people start to lose interest as the reading level goes off the top of the Fog Index. I’m not saying you have to dumb it down… just speak to people in their own language, and save the “thus”es and “invocation”s for your doctoral thesis. {smile}